Canada encompasses nearly a quarter of the world’s remaining forested wilderness. Among the wildlife species most emblematic of Canada‘s wilderness are its caribou: Peary, Barrenground and Woodland. Of these, only the Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) ranges south into forested regions where its various ecotypes span boreal Canada from Newfoundland to the Yukon, and southwards in the mountains to British Columbia. These last caribou, different from their arctic and boreal cousins, inhabit snowy regions where the settled winter snowpack can exceed 2 or 3 metres – hence the name “Deep-Snow Mountain Caribou” or, for convenience, “Deep-Snow Caribou”.

For reasons known only to themselves, professional caribou biologists refer to Deep-Snow Caribou by names that create more confusion than clarity. The name currently in use calls them the Southern Group of the Southern Mountain Caribou – not to be mistaken for the Northern Group of the Southern Mountain Caribou or for that matter the Central Group of the Southern Mountain Caribou, both of which inhabit regions of shallow winter snow, not deep snow.

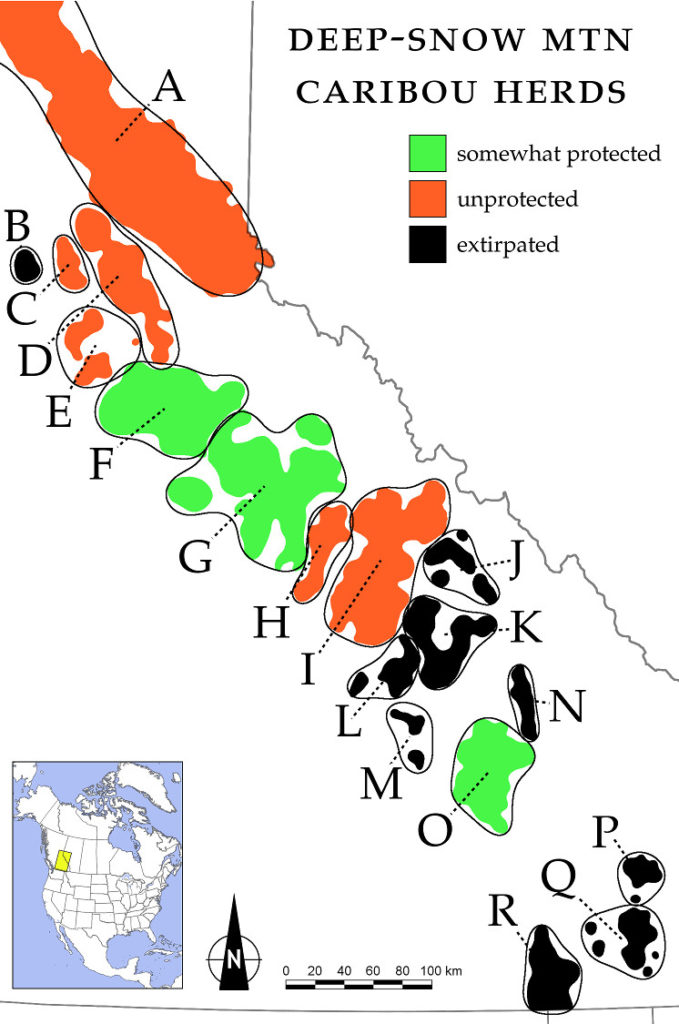

Little more than a century ago, Deep-Snow Caribou occupied a vast range extending northward into central BC and southward into Washington, Idaho and Montana. Currently their range covers less than half this area, and they themselves have splintered into several herds. In 2019, the southernmost herd, which formerly ranged south into the United States, was declared extinct. In Canada, these caribou are currently assessed as ‘endangered’ by the Committee on the status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada and as ‘threatened’ under the federal Species at Risk Act. As of 2016, the total population stood at about a thousand animals.

Forty percent of the world’s Deep-Snow Mountain Caribou disappeared between 2007 and 2016 – largely a result of the BC government’s 2007 Mountain Caribou Recovery Implementation Plan. Here are the latest available estimates for the 18 herds that existed in 2005, including nine herds (in black on the map and in italics below) that have since blinked out. (A) Hart Ranges (375 individuals); (B) George Mtn (0); (C) Narrow Lake (36); (D) North Cariboo Mtn (146); (E) Barkerville (72); (F) Quesnel Highlands (200); (G) Wells Gray South (111); (H) Groundhog (19); (I) Columbia North (147); (J) Central Rockies/Kinbasket (0); (K) Columbia South (4); (L) Frisby-Boulder (0); (M) Monashee (0); (N) Duncan (0); (O) Central Selkirks/Nakusp (25); (P) Purcells-Central (0); (Q) Purcells-South (0); and (R) South Selkirks (0). The three herds in green broadly overlap with existing protected areas and for this reason must be cornerstone to any viable conservation strategy for Deep-Snow Caribou.

Living in regions of deep snow means that Deep-Snow Caribou have little or no access to ground vegetation in mid-winter through late spring. During this season they must either descend to elevations where the snow is less deep or, especially in late winter, turn to tree-dwelling hair lichens as a virtually exclusive food source. For up to five or six months each year, these caribou walk on top of the winter snow pack, searching for hair lichens within foraging reach.

Dependence on hair lichens as winter food imposes some limitations. First, hair lichen biomass accumulates slowly in forested habitats within the range of Deep-Snow Caribou. The reasons are complex, but generally a forest must be older than about 120 to 150 years to support hair lichen loadings in quantity adequate to their foraging needs. Second, arboreal hair lichens don’t grow at heights below the settled depth of the winter snowpack. In areas where the winter snowpack exceeds about 2 m, this means that hair lichens can be inaccessible to caribou until the snowpack forms a feeding platform sufficiently deep to reach them. At such times, they must often descend in early winter to lower elevations where the snow is not so deep, where hair lichens grow closer to the ground, and where they can paw the snow for ground vegetation. The upshot is that Deep-Snow Caribou herds that occur in snowy regions need access to oldgrowth forests at all forested elevations. Because old forests are little used by large predators, large tracks of oldgrowth also provide needed spatial separation between caribou and the wolves and cougar that predate on them.

Dependence on hair lichens as winter food imposes some limitations. First, hair lichen biomass accumulates slowly in forested habitats within the range of Deep-Snow Caribou. The reasons are complex, but generally a forest must be older than about 120 to 150 years to support hair lichen loadings in quantity adequate to their foraging needs. Second, arboreal hair lichens don’t grow at heights below the settled depth of the winter snowpack. In areas where the winter snowpack exceeds about 2 m, this means that hair lichens can be inaccessible to caribou until the snowpack forms a feeding platform sufficiently deep to reach them. At such times, they must often descend in early winter to lower elevations where the snow is not so deep, where hair lichens grow closer to the ground, and where they can paw the snow for ground vegetation. The upshot is that Deep-Snow Caribou herds that occur in snowy regions need access to oldgrowth forests at all forested elevations. Because old forests are little used by large predators, large tracks of oldgrowth also provide needed spatial separation between caribou and the wolves and cougar that predate on them.

More information on the life history of Deep-Snow Caribou appears in this engaging account by Trevor Kinley.

Deep-Snow Mountain Caribou “Conservation”

Crucially, all remaining large Deep-Snow Caribou herds inhabit the Caribou Rainforest (also Inland Temperate Rainforest) where wildfire is rare and oldgrowth forests, until recently, correspondingly extensive. For nearly half a century, beginning in the 1970s, corporate logging has incrementally transformed these oldgrowth forests into a vast checkerboard of cutblocks, remnant oldgrowth patches, and the haul roads that interlink them. This has had four adverse impacts on these caribou.

First, clearcuts produce more habitat for deer and moose, and therefore promote increased predator populations, which in turn can secondarily predate upon caribou. Second, progressive clearcut logging reduces spatial separation between caribou and their predators, hence increasing the likelihood of predation. Third, clearcut logging in its later stages can make finding sufficient winter food difficult for caribou, especially given their reluctance to use patchy stands. Winter starvation can in turn lead to reduced calf survival the following spring. Finally, extensive logging roads provide access to snowmobilers and raises the spectre of poaching.

Proponents of industrial forestry often speak of “habitat recovery” as though oldgrowth forests logged within the past few decades will soon once again provide habitat for Deep-Snow Caribou. This is nonsense. As mentioned, a logged (or burned) stand will not support caribou for well over a century. At current rapid rates of population decline, most herds will disappear long before today‘s clearcuts mature to oldgrowth status. In effect, each new clearcut removes a portion of their total habitat permanently. Hence clearcut logging is in this regard more like mining than like logging.

In 2007, the BC Liberal government under Gordon Campbell introduced its Mountain Caribou Recovery Implementation Plan, which committed to recovering DSC to historic numbers through aggressive predator control coupled, incongruously, with allowance for intense logging of their lower-elevation habitat used in early winter. Thirteen years later, the most immediate outcome of this plan is a 40 per cent decline in the global population.

In 2018, the B.C. NDP government under John Horgan announced a new recovery plan which, unfortunately, scarcely differs from the one that proceeded it – and will likely be just as successful. Here again, the focus is on predator control, to which has been added maternity pens (= fenced areas for pregnant cows) and increased hunting of moose and deer where their populations exceed certain upper limits. Habitat protection, meanwhile, is off the table, while logging is to continue as usual.

To cut to the chase, it seems fair to say that Deep-Snow Mountain Caribou are once again knowingly being pushed to oblivion by British Columbia’s elected officials. Tragically, Canada’s federal government under Justin Trudeau is complicit in this outrage against the public interest. For more on this, link here and here.