Systemic job loss in forest-dependent communities in interior British Columbia has nothing to do with Deep-Snow Mountain Caribou.

Rather, it has to do with multi-national corporations who have forced local communities to sacrifice forest sustainability to the bottom lines of their wealthy shareholders.

Here, professional forester Anthony Britneff dispels the myth of the “working forest” and points the way to a renewed relationship between local communities and their forestlands.

The forest sector has deep roots in rural British Columbia with multi-generational families working in the industry either directly in logging or in related businesses like selling logging trucks. Continued forest industry decline threatens a long-established way of life for those relatively few people remaining in the sector.

The forest industry’s decline began in 1988. Since then, that decline has been exacerbated by the impacts of the mountain pine beetle epidemic and by a shortage in timber supply owing to unsustainable logging, wildfires and forest health issues related to clearcutting and climate change.

Since 1988, the forest industry has contracted radically. The pulp mills that once stood in Prince Rupert, Kitimat, Ocean Falls, Port Alice, Campbell River, Gold River, Tahsis and Woodfibre are long since gone. Since 2000, over 80 sawmills province-wide have been shuttered. Mining, not forest products, is now B.C.’s largest export sector.

Rural British Columbians have dealt with, and adapted to, massive job losses in the forest sector over the last three decades. In 2000, jobs in forestry, logging, support services and wood-products manufacturing numbered 101,000. Since then, over 55,000 jobs have been lost.

The industry’s once-proud claim that forestry paid for healthcare and education is now illusory. Government revenue reporting shows that forestry does not pay its own bills never mind underpinning social service expenditures. The forest industry now accounts for a mere 2 per cent of provincial gross domestic product.

The choice for industry was clear and it decided on its strategy years ago: maximize short-term profit; invest profits in mills overseas as the best of the old-growth forests are logged; shutter mills; and sell associated assets and working forest (tenure).

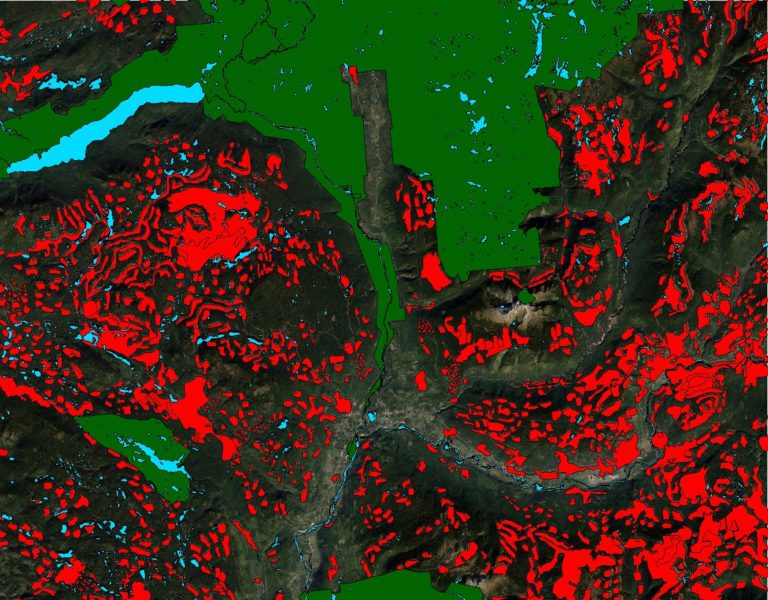

This overview of clearcut logging adjacent to southern Wells Gray Park dates from 2004. Much more has been cut since then, meanwhile leading to a 40% loss of the Wells Gray South Deep-Snow Caribou herd. In 2019, the local mill permanently closed, putting nearly 200 people out of work. All this with thanks to the environmental policies of BC governments past and present – and with the able assistance of industry and, tragically, countless ethically compromised resource professionals.

Forest-dependent British Columbians have a choice between two options for their future: to maintain the industrial status quo and suffer further decline or to collaborate with government in changing how forestry works in B.C. and reap the rewards of forward thinking.

Ninety-four percent of B.C. remains public land. By retaining public ownership of the land, British Columbians keep open their options for land use compatible with timber production. This allows for diversified local economies.

The forest industry has had a “working forest” since the beginning of the 20th century. It is called the “tenure system”. Unlike the Agricultural Land Reserve (ALR) from which land can be removed for other uses, timber volume or land cannot be removed from a forest tenure holder for other uses without compensation.

So, with security of timber supply in place, why do some rural British Columbians sign petitions for a “working forest” at the behest of the Council of Forest Industries and the BC Forestry Alliance? They do so not recognizing that the forest industry already has a working forest and blind to the industry’s hidden agenda, which is to privatize forest land.

That said, the present working forest or tenure system does badly need revamping to take away control of public forests from an oligopoly of multinational corporations and to place it in the hands of local forest trusts. This would require removing large corporate industry from the woods and having it do what it does best, which is manufacturing, not forestry.

Regional log markets would allow mid-sized and small manufacturers to access the available supply of timber. Local residents would find employment both in the woods under the administration of local forest trusts and in private sector manufacturing plants — niche, value-added and primary.

A forester general would report to the legislature and have powers to set standards for regional forest practices, to audit the activities of local forest trusts and regional log markets, to oversee regional research, and to provide the legislature with detailed, annual forestry reports.

Change in the governance of forests along these suggested lines would preserve a rural way of life now badly threatened by maintaining the industrial status quo. Such change would be focused on local economic and environmental well-being.

This vision would be achieved by re-writing forestry laws based on the principles of sustainability and conservation, of local forest administration, of open access to timber, and, last but not least, of reliance upon the will of rural British Columbians to change, survive and succeed.

Anthony Britneff worked for the B.C. Forest Service for 40 years holding senior professional positions in inventory, silviculture and forest health.